Mark Pickard. Ultra Running Pioneer.

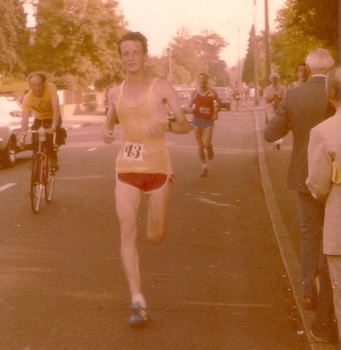

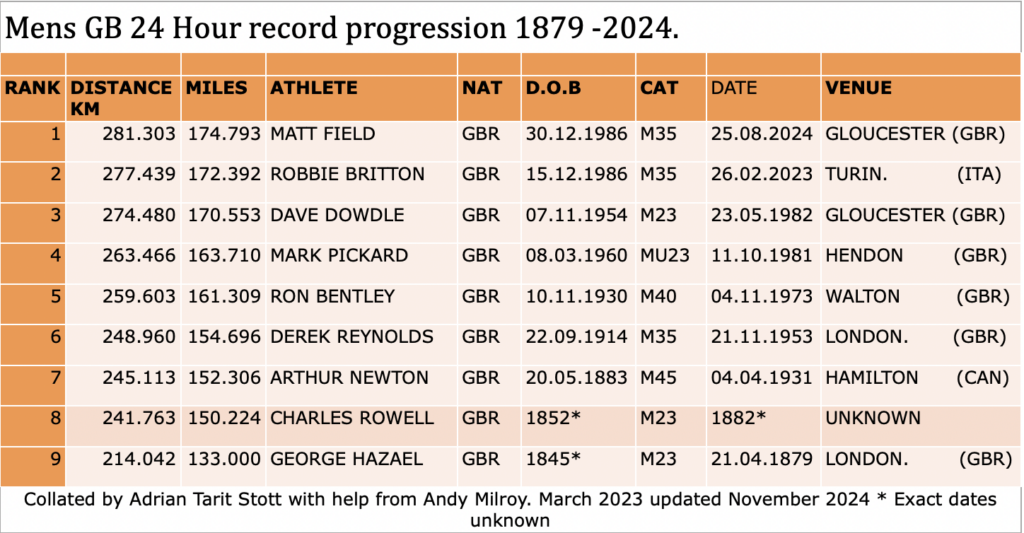

Mark Pickard was a genuine ultra running pioneer. In September, I wrote a blog Comparing Matt Field’s new British 24-hour record with Previous marks. A couple of weeks later, Mark Pickard contacted me to tell me that I had missed him off the GB 24-hour record progression list that I had included. When checking, I discovered that I had made a schoolboy error in uploading the wrong table to the post.

I recall I had finished that blog hurriedly, before going off to help at the Sri Chinmoy 3,100 mile race in New York. Mark, identified a couple of other errors too which I was grateful for.

Long story short, together with correcting the record, I took the opportunity to arrange to talk with Mark and chat about some of his amazing exploits when he was very young! He was, like many others back in the 1970’s and 1980’s, a young ultra running pioneer. Trying to figure out how best to train for ultra marathons on raw enthusiasm and a love of running.

As you read on to hear of some of those exploits, his very unique training and racing approach will become more apparent. Looking back now, he would agree that his approach to training and racing wasn’t too structured or scientific, but he achieved some phenomenal ultra performances, when only in his early twenties.

Early long distance walking and running exploits.

AS. Just backtracking a little. You seem to have been taking part in LDWA events since an early age. Can you elaborate on how you got into long-distance walking and then, how that developed into running?

MP. Yes, I started walking at a young age with my parents. We used to go up to the Lake District or Wales for holidays. I think I was seven the first time I went up Snowdon. My parents were members of the Croydon group of the Ramblers Association. The Ramblers used to enter people for the Tanners Marathon each summer, which was a 30-mile challenge event. You have 10 hours to cover 30 miles. I got talked into doing that in 1976, which you might recall, was a very hotyear.

I hadn’t done any training or anything. It’s about 12 miles from where I lived, so I got on the bike and cycled up to the start. I jogged for about seven miles and then walked the rest.

AS. And how old were you then?

MP. 16. I was born in 1960. March 8th 1960, to be precise.

Of course, I then had the problem of having to cycle home again. I was so exhausted. It had taken me 8 hours and 28 minutes, butI was determined to try and do more of these long events. Next, I did the Chiltern Marathon that year, another challenge event. Then I saw the Masters and Maidens Marathon advertised in Guildford, which in its day was something of a novelty because it had a five-and-a-half-hour time limit.

NOTE: Before the advent of mass participation events, marathons were usually the domain of the regular club runners, with most finishing in well under 4 hours, and the majority, under three hours. The Masters and Maidens marathon was the brainchild of Alan Blatchford of the LDWA, who created a welcoming marathon for slower runners based around roads in the Guildford area. Entry to the Masters and Maidens was open to anyone except men between the ages of 20 and 40, who had previously run the distance under 3 hours. It was a rare opportunity for slower or older runners to tackle the classic marathon distance, before Mass participation marathons started appearing in the UK, in the early 1980’s.

MP. The Master’s and Maidens was a standard road marathon with a five-and-a-half-hour time limit. I decided to enter. I had started at Sixth Form College in September, the marathon was held in October. Just before the race, I’d managed to fall off a trampette and crack some bones in my wrist, so I’d actually got my arm in plaster from the elbow down to the wrist when I ran that marathon. I cycled down to Guildford for the Masters and Maidens as I could still use my fingers to grip. I had no idea what I was doing. I mean, I’d got a packet of cigarettes and a map and compass to give you an idea of my state of preparation. Anyway, that took me I think, 5 hours, 17 minutes and 46 seconds.

That was my first marathon experience.

AS. Am I right in thinking that was still in the days when you had to be 21 to even attempt an official road marathon?

MP. That’s right. Although Alan, the race organiser, allowed younger runners to take part.

I was absolutely desperate not to be timed out, and I remember that some St John’s Ambulance people were trying to get me into the ambulance at one point. Anyway, after my first Masters and Maidens, I remember just being so pleased to have finished. Alan Blatchford was somebody that I looked up to and aspired to be like. Somebody who had actually run a sub-three-hour marathon. To a young 16-year-old, he was some kind of superhero and he even signed my plaster cast.

That wasn’t a very auspicious start, but I decided that the next year, in 1977, I would run the Masters and Maidens again. People like David Rosen and Frank Thomas were also people who really inspired me as well in the early days of trying to run.

The following year, I decided I was going try and run inside four hours at the Masters and Maidens. That was in 1977, which I did. I think I ran 3:39:54.

I was taking part in many challenge events with the LDWA. In the early part of 1977, I did the Surrey Summits 100km overnight challenge walk. Running was not allowed in this event and it took me 22 hours and 21 minutes. That’s basically how things started. I started off doing the challenge events. Because they were very free and easy, go as you please, with most of them allowing running, or you can mix a bit of running in with walking or jogging.

When I started running road races, the distance didn’t really hold any fears for me. I mean, I’d covered long distances at quite a young age. It was just a question of whether I could actually run them rather than walk them.

I joined Epsom and Ewell Harriers because Alan Blatchford was a member. Graham Peddie was also. They were both members of the Long Distance Walkers Association as well as competent runners.

AS. When did you first run an official road race or road marathon marathon?

MP. In 1978, I entered the Masters and Maidens marathon again. However, I had done the 50-mile Longmynd Hike the day before at Church Stretton, and I didn’t get back to Guildford in time.

Somebody suggested I should try the Walton 10-mile race, one of many road races around then. I had no idea what time I was going to run, but I ran that the following weekend, and I think I ran 58.26. Then I ran the Bracknell 10 and the Epsom 10, and they were both inside the hour too. Next, I ran the Barnsley Marathon that December. I had been too late to enter officially, but ran with another runners number who was unable to run on the day. That was the first official road marathon, and I ran two hours, fifty minutes and nine seconds. I felt really terrible in the later stages. In retrospect, looking back on what I know now, I actually had hypothermia towards the end of that race. I mean, at the time, I didn’t know what had gone wrong because I thought I’d just gone out too fast and blown up, which to some extent I had, but having run when really tired with muscle-glycogen depletion and everything else I know now, I know that I was suffering the early stages of hypothermia. That race was in December 1978.

The following year, 1979, I ran the one race I failed to finish, the Newport to Tredegar 22-mile road race in South Wales. I actually collapsed with hypothermia. So I know what that basically is and what it feels like.

“I wouldn’t say my training was ever structured.”

AS. Is it right to think you are getting into more structured training now?

MP . Yes, in some ways, though I wouldn’t say my training was ever structured. I wasn’t at all scientific in the way I trained. I used to try and run every day. Every day that I was capable of running, I went for a run. By the time I was running regularly in 1978 and early 1979, I was running about six miles a day as fast as I could.

I was going pretty much, you know, sort of eyeballs out every day. That probably isn’t the best thing to do. But you know, I never kept a training diary.

AS. How often were you racing then in the late 70s? Were you a prolific racer already, or was it just something that evolved?

MP. I ran a lot of races in 1979, more than any other year. I didn’t really like training. I just used to train to be able to race or take part in a challenge event.

I mean, I would lump the challenge events in almost the same class as road races, as an organized event,

If there was something to do at the weekend, I would do it. That’s what it boiled down to.

AS. When did you do your first serious ultra race?

MP. My first ultra race was the Two Bridges in 1979. I finished 7th in 3:42:01 when I was only 19.

The following weekend, I ran the South London Harriers (SLH) 30

and finished 9th in 3:13:34. I was sick as the finish came into sight.

I think my parents had gone on holiday and left some milk in the fridge and I’d made a milkshake. I was still a little inexperienced and didn’t really know what I was doing. I’d thought rather than let the milk go to waste, I would drink it. I was sick just as the finish came in sight and decided the milkshake was the cause. That race was 30 miles 616 yards, in 3:13:34, which wasn’t a great run.

I then ran the Rugby marathon the following day in 2:52:43.

I actually ran the SLH 30 / Rugby Marathon ‘double’ in 1979, 1980 and 1981, and in 1981 I again ran the Two Bridges the previous weekend.

AS. In later years, you would have come back and won the Two Bridges.

MP. Oh yes. In 1981 I won it.

I also ran the London to Brighton that year (1979). They had to alter the course slightly that year, and it measured 54 miles, 460 yards. I ran 6:01:31 and finished 10th.

I actually wanted to run the 24-hour at Crystal Palace that year, but due to the fact I was only 19, I was not allowed to enter.

I remember calling into the race on the way home from the Harlow Marathon that I had run on the Saturday. I just stood watching the 24-hour race for a couple of hours and was fascinated by it.

AS. So. Even though the official age limit for marathons and ultras was 21, you were being let into them, and people were turning a bit of a blind eye.

MP. Yes, I think you still had to be 21 at that stage, wasn’t it? I mean, I managed to get into the London Brighton race somehow before I was 21. I can’t recall when they lowered the age you could officially run a marathon to 18.

AS. I think that was the mid-80s, 1985 or 86 I think.

MP. The first 24 hours I ran, I was 20 in 1980. I ran the Blackburn 24. I’d contacted Dave Jones, the organiser, and asked, “Are you going to let me run?”

He said, “As far as I’m concerned, if you’re good enough you’re old enough.” and he let me run.

Towards the end of 1979, I was getting reasonably fit.

I got inside 2 hours 30 minutes at the Barnsley Marathon with 2:28:40.

I ran the Newport to Tredegar 22 in December 1979, which I ran in a mesh vest. It was my one and only DNF. I collapsed with hypothermia just over a mile from the finish. I vaguely remember falling over once and getting up again, but the second time, I don’t even think I put my hands out to try to protect myself.

Martin Daykin’s wife was following the race and wrapped me up in his tracksuit until the ambulance came. I ended up with eight stitches in my chin and chipped teeth (and spent the night in hospital).

NOTE: Martin Daykin was also a leading ultra runner of the time. Part of the famous Gloucester AC group of ultra-runners.

That was a bit of a disaster really.

In the early part of 1980, I got injured. I didn’t have a very good year in 1980 in terms of times and things. I struggled with injury and some problems with my hip.

I had a pretty awful run at the London-Brighton. I was slower than I was the previous year, on the same lengthened course due to long-term roadworks, but I had a really stinking cold the week before.

NOTE: Mark finished 13th in 6:06:00

Then I ran in the 24-hour at Blackburn, the one where Jean-Giles Boussiquet broke the world record. He ran 264.108 Kilometres /164.109 Miles. That was also the race where Mike Newton broke the 200km world record when he ran 16 hours 42 minutes and 31 seconds for 200 kilometres.

Mike struggled a bit after reaching 200km and finished second behind Boussiquet. I finished third.

I remember Don Turner telling me late in the race that as long as I kept moving, I would get over 150 miles. I finished up with 150 miles and 1,447 yards. (242.725 Kilometres)

AS. Quite an achievement at that age.

MP. Yes. I was 20 then.

I mean, the irony is, although it is all sort of speculation. If I’d been allowed to run a 24-hour the previous year at Crystal Palace, I’m not saying I could have gone any further, but 12 months previously, I was definitely fitter and might have been able to go further.

In terms of what I could run for a marathon, I was certainly fitter in 1979 than I was in 1980. But anyway, that’s pure speculation.

AS. Fast forward another year to 1981. And you ran that spectacular 263 kilometres for a new British Record

MP. Yeah, 263.466 Kilometres, 163 miles 1249 yards

AS. Tell us how that race unfolded. By now, you have experienced the close reality of what a 24-hour race is. You’ve watched them, and you’ve taken part in one. You obviously had more confidence going into this one. How did it unfold?

MP. It didn’t go terribly well. I mean, I think I found it difficult to run slowly enough at the start. In retrospect, I should have been more disciplined in training and made myself get used to running at a slow pace. My training at that time was basically running twice a day. I used to run nine miles in the morning and seven at night,

It was all quite fast, around five and a half minute milling.

In the early stages of the 24-hour, I felt okay, but by about 110 miles, I was starting to stiffen up in my knees, my ankles and my groin. My great strength when I was young was I didn’t generally get stiff. I had run at Gloucester in April 1981 in the Gloucester 100-mile race and ran 14:13:50, which wasn’t very good, for 4th place.

I had a fairly bad year in 1980. After the 24-hour race at Blackburn, I still wasn’t feeling too good. Early in 1981, I was beginning to get fit, perhaps in terms of speed, but I hadn’t really got the background to run long distances very well.

The day after the Gloucester 100, I ran the Finchley 20 in 2:04:27. I think if I remember right. I’d actually gone through 10 in the Finchley race just inside the hour, but I did struggle a bit after that. I remember feeling quite heavy-legged but not stiff as such.

I mean, going back to how that feeds into the 24-hour race, as I said, when I was young, running distances up to 100 miles didn’t really have any reaction the following day at all in terms of stiffness. However, on the three occasions I did 24-hour races of 150 miles plus, I was absolutely crocked. The following day, my legs were solid.

The difference between 50 and 100 miles in terms of recovery was quite small. The difference between 100 and 150 miles was enormous. Going back to the 24-hour, I was reasonably quick through 100 miles in 13:03:51. It all went a little downhill after that. It was fairly cold overnight, and at one point, I had to get off the track and go inside to the toilet. Coming out again into the cold didn’t help, and it took a while to get going again.

AS. Obviously, things have changed in the modern era, but what sort of things were you fueling with? How often were you fueling in a 24-hour?

MP. Drinks-wise, I had de-fizzed cola. I took the top of the bottle off and put some more sugar in, perhaps to let the fizz out. I also had lime squash, blackcurrant squash, and coffee sometimes. I didn’t really eat anything. The only thing I used to eat on the long runs were Jaffa cakes.

AS. Okay.

MP. I found those soft and easy to get down. I had found from experience that I couldn’t eat before a race, or if I did, I was going to suffer. Going back to what I said about the SLH 30 in 1979 and the milk. I mean, what I found was that I needed to race on an empty stomach. I can remember the Two Bridges in 1981, where they put you up at the naval base in Rosyth.

They laid on a breakfast, but I didn’t touch it. I didn’t eat anything on the morning of the race, but I made a pig of myself the day before. People were saying, “If you don’t have anything to eat, you won’t get very far, and of course, I mean, I won the race, which is the best way to prove people wrong.

So, as far as eating before races were concerned, if I hadn’t got a clear four hours before the start of the race, I wouldn’t eat anything. Fortunately, in the 1980s, marathons used to start at a civilised time, like two o’clock in the afternoon, so I could normally get up, have a light breakfast and travel to the race and things. With the ultras, if they were starting early, then I wouldn’t eat in the morning at all. I found with the really long races, like the 24-hour races, once I’d started running and slowed down, I could tolerate a limited amount of food, but it was basically just the odd Jaffa cake. It’s so long ago now, but possibly I had some sweets or Jelly Babies as well. I mean the only thing that really sticks in my mind is Jaffa Cakes.

AS. You mentioned that the 24-hour races took longer to recover from compared to the 50 and 100 milers. How long did it take you to recover from something like running 260 kilometres?

MP. Well, the weekend after I ran the 263 kilometres, I took part in a Long Distance Walkers Association event. There’s a Wealden Waters walk that was 100km. You could run or walk, and I actually took the run start. There were only 2 of us on the runner’s start.

Taking the runners’ start meant that I had three hours less daylight than the walkers which exacerbated the navigational problems. This, together with torrential rain, copious amounts of mud and fatigue, resulted in a very slow time of 20 hours 31 minutes. Some of those who took the walkers’ start were faster.

The following weekend, a fortnight after the Copthall 24-hour race, I ran 2:26:06 at the Harlow Marathon.

AS. So it didn’t take you that long to recover!!

MP. In terms of recovering from what it actually did to my body, I don’t think I ever properly recovered from the Copthall race.

In terms of being able to run with some semblance of normality, it would have been several days. Whereas, what I was saying is, if it was a 50-mile or a 100-mile, I could go out and run, fairly normally, the following day. There’s no way I could run anything like normally the day after the 24 hours.

AS. The fact is that back then, you were all pioneers. Runners like Don Ritchie, Cavin Woodward and Mike Newton were all just discovering how to train for ultra races and inevitably over-racing.

I knew Donald very well being up here in Scotland, and I remember asking him in later years, “Would you change anything if you knew now what you knew then?” He said something along the lines of, “Well yes. If I knew now what I knew then I probably would train a bit smarter, but I wouldn’t change anything, and I don’t regret anything I did. We were all finding out about ourselves all the time and what we could achieve.”

MP.Yes. I wasn’t at all scientific or anything in the way I approached training. I just used to train so that I could take part in the events at the weekends. Would I have done it differently? I mean, I would have liked to have broken 50 minutes for 10 miles and broken 2:20 for the marathon. I didn’t achieve either of those goals. I missed the 10 miles by the grand total of three seconds at the Reading 10, and the best marathon I ran was 2:21:24, at Sandbach in June 1981 so you know, if I trained a bit smarter and planned what I was doing a bit better, I might have got faster times over the more conventional distances.

AS.Picking up on that 50 minutes and 03 seconds at the Reading 10 Miles.

Was that on that infamous 1981 London to Brighton weekend?

MP. Yes, it was.

AS. So that was your 10-mile PB on Saturday, which was followed up by…Well, just tell the story about the following day, the London to Brighton race and who you were racing against.

MP. I came up against Bruce Fordyce, and I finished second!

NOTE: The South African Bruce Fordyce was probably the best ultra runner of the time. In 1981, he was already an established talent, having won the Comrades Marathon in June of that year. This followed up on his 3rd place in the 1979 Comrades and second place in 1980. As well as a hatrick of London- Brighton victories in 1981-82-83, in 10 years between 1981 and 1990, he recorded nine victories at the famous Comrades Marathon in South Africa, missing the 1989 race through injury.

AS. You ran the 50-minute, 10-mile on the Saturday. I am imagining back in 1981, it would have been an afternoon start.

MP. Yes, yes, it was an afternoon.

AS. You get home and have a bit of supper. You get some sleep. Then get yourself down to Big Ben for the first strike of 7 am on Sunday.

NOTE: The London to Brighton road race was the classic British ultra race for many years before increasing traffic, combined with an ageing organising team and a lack of younger people coming forward to assist, contributed to its demise after the 2005 race. It started on Westminster Bridge, right below Big Ben. The first chime of 7 am was the signal for the race start. You then ran to Brighton to finish on the seafront at the Aquarium . Up until 1984 it was run on very busy roads, principally the A23. From the 1984 race onwards, due to increasing traffic, the route was altered via a mixture of busy main trunk roads and some quieter country roads. In later years when it crossed Ditchling Beacon on the South Downs, it finished on the side of ‘The Level.

MP. I think I actually stayed with a clubmate fairly close to the start.

I’ve got a feeling I stayed overnight with Mick Coventry at Banstead.

The Reading 10 was an afternoon race with a notoriously fast course too.

I actually ran a faster average pace in the Greenwich 11-mile race that year. I ran the Greenwich 11 in 54.29 and won that. That was 142 yards over distance as measured by the RRC. So that’s well inside five-minute miling, but they didn’t take a 10-mile split.

AS. So you weren’t intimidated being on the start line with Bruce Fordyce?

MP. I didn’t know a huge amount about him because I just used to do my own thing anyway. It never particularly bothered me whether I won or not. I wasn’t super competitive in that sense. I do remember struggling in the last quarter of that race.

AS. But you were neck and neck with Fordyce well past halfway through that year!!!

MP. Yes, it was somewhere around about 40 miles, around Bolney, he got away from me, I think.

AS. Just when the hills start on the Downs.

MP. Yes. We were still essentially together at the Bolney checkpoint. That was 39 miles, 1,227 yards, and, according to the results, he was a second ahead of me there. It was after that he began to pull away. He finished with 5:21:15. I ran 5:24:55.

AS. Lots of people would be very happy with that.

MP. I was happy, but I have to say, I didn’t rate it as my best performance.

I would have to say the 24-hour at Copthall because it was a UK national record at the time and put me second on the world all-time list behind Boussiquet, who had two longer runs, the better one being 169 miles 705 yards / 272.624 kilometres in May 1981

I think the Two Bridges win in 1981 was probably about as good as it gets really for me. 3:26:01 for 36 miles 158 yards

AS. Well, you did win the Two Bridges that year. Did you value that more so than your Brighton victory?

MP. Yes, to be honest, My Brighton victory was later in 1988. That was a funny old race with poor weather and a relatively weak field. Although I won it, it was a very slow time. The performance wasn’t anywhere near as good as the performance where I finished second to Bruce Fordyce in 1981. I wouldn’t swap the Two Bridges win for that win in the Brighton. It was about 6:06:25 I think, much slower than the 1981 race with Fordyce when I ran 5:24:55

.I was much more focused on times and having a good race than winning positions in terms of how I rate a performance.

There is some truth in saying that you can’t do much more than beat people who turn up on the day, but it doesn’t mean much unless you’re a top world-class runner and you’re racing against people capable of running world-class times. I would certainly rate my 2:21:24 marathon, where I finished 12th, as worth more than a marathon I might have won at a more low-key event in 2:30 or even 2:40.

AS. Winding the clock forward several years, there has been a resurgence in 24-hour running. It’s almost like the 24 hours as an event became static for a while. There might have been a Kouros effect with his phenomenal distances putting people off, thinking we can’t challenge that.

NOTE: Re. Yiannis Kouros. The Greek runner rewrote the 24-hour record books in the 1980s and 1990s, pushing the world record up on several occasions to become the first runner to break 300km with 303.506 Km in 1997.

AS. In the last 10 years, there has been a resurgence in 24-hour racing generally, with some very good British guys coming on the scene.

How do you feel about the general revival of these distances? People are now running further than the runnes of your era. Donald and Dave Dowdle were surpassing your record distance 30-40 years ago, but no one really challenged those distances for many years. Now since 2022, six more runners have gone further than your 263.466 Kilometres.

MP. I hadn’t kept up to date with what had been going on. I mean, I was surprised when I found out that Alexandr Sorokin had beaten what Yiannis Kouros had done.

It was only by chance that I became aware because I went walking in Wales with an old friend, Walter Hill. I think that was two years ago. When 24-hour racing came up in conversation, I think I said to him that I thought I was still third on the UK all-time list.

Walter checked it, and I think it was true at the time. It was later that year in the 2022 European Championships when the three British runners beat my distance in the same race.

NOTE: Dan Lawson, Paul Maskell and Dan Hawkins were the three British runners in question.

I think that was the first time anyone had beaten my distance since Don Ritchie had in 1990, and again in 1991.

I remember also mentioning something to Walter about Yiannis Kouros. I think he said to me, “Well, you know that has been beaten now.” I wasn’t even aware of that, which shows how out of touch with things I was.

I guess people are training a bit smarter now and working on their nutrition better. There’s been quite a lot of talk and quite a lot of controversy about shoes as well.

I mean, that girl, what was it, ran 2:09:56* for the marathon recently. It was a phenomenal run, so you don’t know how much of that is down to the shoes. We can only speculate.

NOTE: *Ruth Chepngetich recently broke the women’s world marathon record in Chicago.

MP. I can remember running the South Downs 80. That would have been, I think, 1988, and I was running with another runner Gwyn Williams. His support crew gave me a special drink. I think it was one of the first long-chain carbohydrate polymer drinks. It was called Leppin.

I was amazed at how good that was, and I thought, “If only that stuff had been available when I was running at my best. I think I would have found that quite useful.

If I had been more scientific about the way I trained and been more choosy, you know, about the races, I don’t know how much difference it would have made. Obviously, the Reading 10 and the London to Brighton weekend were only a fortnight before the 24-hour, and In between them, I ran the Wimbledon 10 on the Saturday before in 51-29 and won the Kent 20 in 1:46:50 on the Sunday.

The weekend before the Reading 10 / London to Brighton, I ran the Nuneaton 10 in 51:45 on the Saturday and the Birmingham Marathon in 2:24:17 on the Sunday.

I never really rested up.

As far as the training went, I didn’t really taper down the training. I didn’t do much mileage anyway. I was running 9 miles in the morning and 7 in the evening all at around five and a half minute mile pace. The day before a race, I would perhaps just run the morning run at a slower pace, about a 6-minute mile pace and then wouldn’t run in the evening at all. I’d justskip the evening run.

This routine was in the summer of 1981 when I was between university courses and not working – once back at university, from October 1981, I normally trained once a day, about 9 miles in the evening, before the Gloucester 24-hour race in May 1982

I ran in the 24-hour at Gloucester when Dave Dowdle broke the world record. I faded pretty badly or faded even worse there than at Copthall. I was 13:10 something at 100 miles. Was it 13:10:43?

NOTE: In that Gloucester 24 hour. Mark had reached 100 miles in 13:10:43, 20 minutes ahead of Dave Dowdle, who recorded 13:31:29. Dowdle would go on to break the existing World 24-hour record with 274.480 Kilometres, which stood as the long-standing British 24-hour record until 2023. Lynn Fitzgerald also set what was then the women’s UK and world 24-hour record with 133 miles 939 yards / 214.902 km

I also received this subsequent note from Mark. “With regard to not resting up, on the two weekends before the Gloucester 24-hour race, in which I managed only 157 miles 515 yards, I ran 2:22:15 in the London Marathon with a 7-mile race in 34:30 the previous day, and then 2:22:02 in the Isle of Wight Marathon)

AS. So, just a couple of questions to close things out. What were your favourite shoes when you were running your best races?

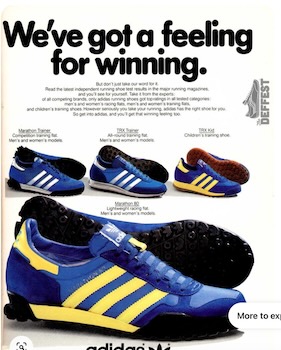

MP. In terms of racing shoes, soon after I first started running races, I was running in a pair of Nike Elite, which I found quite good. In 1981, I got a pair of Adidas Marathon 80’s. They were one of the first really lightweight racing shoes that gave cushioning that was comparable to a trainer. Because some of the racing shoes in the earlier days weren’t much more than plimsolls, were they?

After I broke the UK National 24-hour record, New Balance asked me if I’d like to wear their kit, and they gave me some shoes. I had a pair of the New Balance Comp 100 and then the Comp 200, but I didn’t get on with those quite as well. They gave me training shoes as well.

As for the training shoes, because I was tall and heavy as a runner, I used to find that the mid-soles on the shoes would collapse, and then you’d run lopsided making injury more likely. There was a shoe called the Adidas TRX trainer. There was the original TRX, and then they brought out the TRX trainer and the TRX competition. The TRX trainer had a polyurethane midsole that didn’t collapse. Eventually, after enough miles, it just split, but that was a real game changer for me, having a shoe that lasted a bit longer and didn’t collapse.

AS. If you were chatting to a young 19-year-old or 20-year-old who came to you and said,” I want to run some ultra marathons.”

What advice would you give your younger self, and what advice would your older self give any budding ultra-runner?

MP. I think, “Don’t do it! (Laughs).

Definitely don’t try and do what I did anyway. I mean, as you probably know, I’ve had quite a lot of seriously badproblems from running. I’ve had ten operations on my left leg and five on the right.

AS, Yes. All are documented in your book very well.

MP. Some of the operations were after I wrote the book. Towards the end of 1982, I developed this pain in the left thigh. It turned out that I’d got a haematogenous staphylococcal osteomyelitis bone infection, and that was a hell of a job to clear that up. I was on antibiotics for months, had three operations, and never, never, never returned to the same level after that.

The chances are that it was due to a combination of overtraining and racing, having totally compromised my immune system with a poor diet as well, possibly in combination with a stress fracture. I mean I didn’t study diets. I lived on junk food in those days.

I’ve had surgery for varicose veins. I’ve had quite a lot of treatment on varicose veins. I had them stripped. I think that was in 1989. I’ve had endovenous laser ablation, and I’ve had washouts on both knees.

I’ve had partial knee replacements (Medial resurfacing), patella osteophytectomies, and a couple of heel spurs taken off the left, but not the ones that grow under, not the plantar fasciitis, but the ones that grow out behind the Achilles tendon. I think they call it Haglund’s deformity, and I’ve had surgery for bunions on both feet and hammer toe on the right foot.

AS. So your advice would probably be not to emulate exactly the sort of training regimes that you and Don Ritchie got up to.

MP. Yes. I mean some of Don’s training regimes were quite frightening.

AS. It’s amazing what you have achieved over the years despite it all. It’s been fascinating chatting. People will be fascinated to read about this.

We didn’t even mention how you used to travel to races, but people can read your book and find that out. Is your book still available, by the way?

MP. I did have some copies left, but I don’t know what happened to them. I’ve possibly got them in the garden shed, buried under piles of junk.

People will have to source it on eBay if there are any on there.

Looking back, that was a pretty conceited thing to do, to write a book, but having said that, various people said that they thought it might be worth doing,

AS. It definitely was.

MP. I’d always said if I got to the stage where I couldn’t run under three hours for the marathon, I wouldn’t bother. I also thought that if I didn’t write it then, in 1995, there were going to be a lot of things that in years to come I won’t remember.

Regarding travelling to races, I had a little Honda 90cc semi-automatic motorbike when I was about 18. I used to travel around to races on that, and sometimes I used to have lifts if anybody was going, people were very kind in giving me lifts.

My dad started to teach me to drive, but he wasn’t a very patient man. He was a regimental sergeant major in the Second World War, so you can imagine what he was like as a driving instructor. He taught me to a reasonable extent, but I got a motorbike and sidecar.

I never felt safe on two wheels and I was never happy on the Honda.

Sidecars are a bit of a handful until you get used to driving them, and although it’s possible to turn the things over, you can’t actually fall off them if you drive them sensibly, so they are relatively safe.

I don’t know if the law is the same now, but then, if you had a motorbike license, you could drive a three-wheeler. So I got this old Reliant Regal that I travelled up and down the country in, getting to races.

That’s probably what you are referring to and the number of breakdowns I had getting to and from races. I had a lot of problems with the Reliant!

AS. Yes.

MP. So I certainly had some experiences with that.

AS. Well, I hope it will inspire some people to try and source your book somewhere.

Mark, it has been fascinating talking to you and hearing all these stories, and I have to thank you once again for getting in touch to correct my errors.

Mark’s book Evidence of a Misspent Youth: An Autobiography of a Maverick Long Distance Runner details the ups and downs of Mark’s running career. It was self-published in 1995

London to Brighton Road race history. Blackheath Harriers archives have a history of this classic ultra HERE.

You can also read a history of the original Two Bridges race in Scotland on the Scottish Distance Running website HERE.

Thanks for reading. If you have enjoyed this post, do see our other ones HERE.

If you have a comment, please feel free to add it below.

If you are inspired by this, or think someone else you know will be, please do what you have to do by sharing. You all know how these things work by now:-) You can also follow me on Twitter and Instagram @tarittweets

Sign up to receive our newsletter alerting you to new posts

Adrian Tarit Stott.

The author is a former GB 24-hour ultra international with over 100 ultra race completions. He has also been involved in organising ultra-distance races for over 30 years. Still an active recreational runner, he is currently a member of UKA’s Ultra Running Advisory Group (URAG) and part of the selection and team management for both Scottish and GB ultra teams. He is also a freelance writer in his spare time, contributing articles and reports to several websites and magazines including Athletics Weekly and Irunfar.