THERE IS A BUZZ AROUND 100KM AGAIN (Part 1)

With Aleksandr Sorokin recently setting a new men’s mark for the 100 kilometres, the classic ultra distance is suddenly back in the spotlight. In this blog, we will look a little in depth at Sorokin’s performance, along with the four fastest 100k times in history. There definitely seems to be a buzz around 100km again.

Before Sorokin spectacularly broke the world 100k record (or maybe the best-performance, which we will come to later) a mere 66 seconds had separated the three previous fastest 100km times.

On April 23rd 2022 at the Centurion Track race in Bedford, England, Sorokin lowered the current record by three and a half minutes to record 6:05:41

As a recap, below are those four fastest times:

Aleksandr Sorokin 6:05:41 Bedford (Track )England April 2022

Nao Kazami. 6:09:14 Lake Saroma (Road) Japan June 2018

Jim Walmsley 6:09:26 Arizona USA (Road) January 2021

Don Ritchie 6:10:20 Crystal Palace (Track). London. October 1978

Progression of the mens 100km record

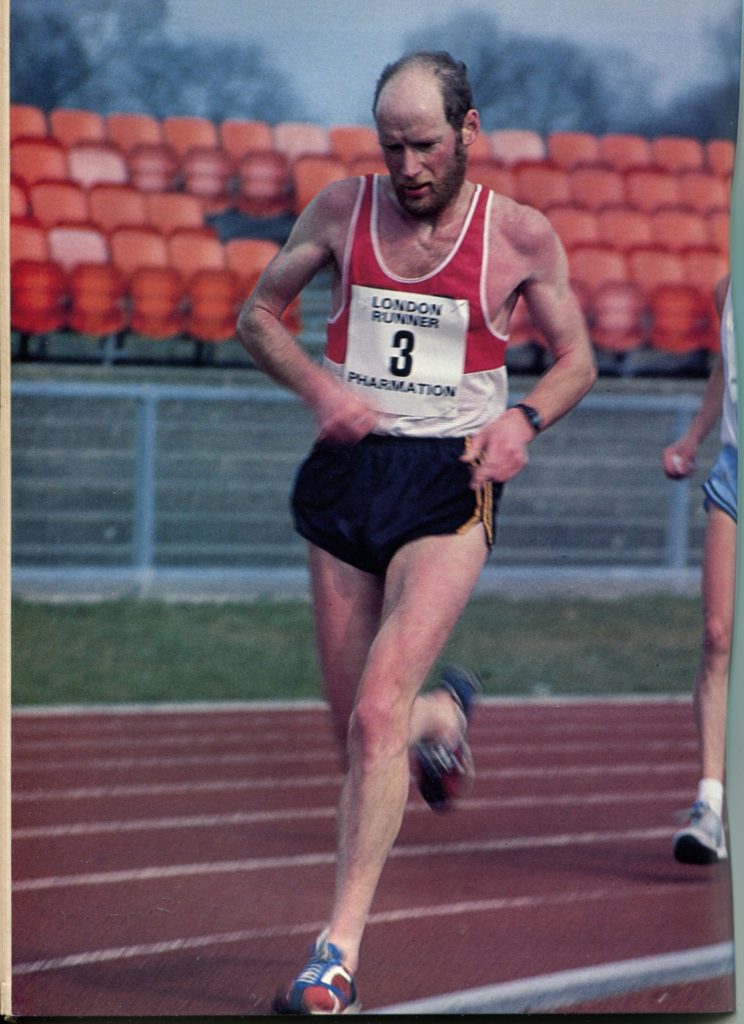

In the mid-1970s and 1980s, the UK was a hotbed of ultra pioneers, with Cavin Woodward and Don Ritchie at the forefront of a group of British men, trading a string of ultra distance records between them. Eleanor Robinson and Hilary Walker were blazing a similar trail for the women.

Woodward set a new mark for 100k of 6:25:28 in 1975 at a track race in Tipton, Birmingham, England. It was the first recorded performance under 6 hours 30 minutes, averaging around 6 minutes 20 seconds per mile/ 3 minutes 50 per km. The run was all the more remarkable as it was a split time en route to an 11:38:54 100-mile time.

Three years later, Don Ritchie, in a purple patch of form, lowered this to 6:10:20, also in a track race at Crystal Palace in London. That phenomenal performance averaged 5.59 minutes per mile (3min 42sec per km) and was to stand for over 40 years. In the intervening time, several extremely competent ultra runners tried to better this mark. They all came up short.

Globally the closest was Japan’s Takahiro Sunada running 6:13:33 in 1998 on the controversially fast Lake Saroma course at Yubetsu in Japan. More of that later too.

Amongst GB runners, Steve Way, in 2014, was to run 6:19:20 on the road in the Anglo Celtic Plate 100km at Gravesend, England, a new GB road record.

Ritchie passed away, aged 73, on 16th June 2018, still holding that 6:10:20 record for the fastest-ever recorded 100km event. In a strange twist of fate just eight days later, on 24th June 2018, that time was finally surpassed by Japan’s Nao Kazami. He recorded 6:09:14, again on the Lake Saroma course.

Fast forward three years to 17th January 2021. In a well-publicised attempt on the 100k record, the American Jim Walmsley ran a very evenly paced race. A new record was in sight with 10km and even 5km to go. However, he faded to finish an agonising 12 seconds short, recording 6:09:26 in Arizona, USA.

Another year forward to April 2022, Alexsander Sorokin runs 6:05:41 at Bedford track England to lower the best-ever 100k mark by a further 3 mins 33 seconds.

So how did each of these runners approach their race, and what were their backgrounds?

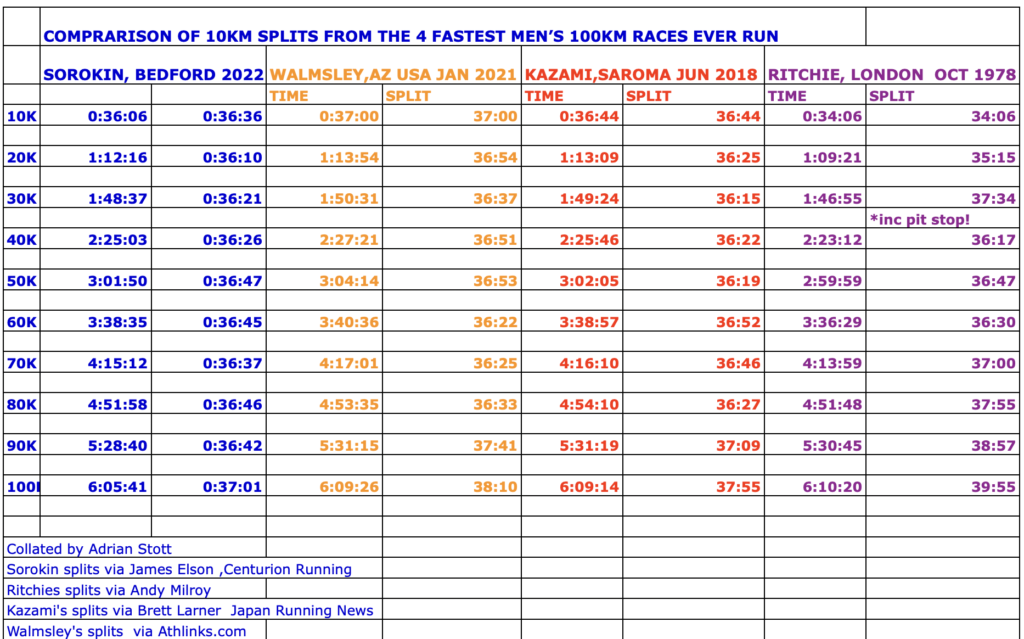

The chart below details the 10k splits of all 4 of these runners in their respective races.

Of the three previous fastest efforts, Kazami was in a lead pack of several experienced 100km runners hitting 10k in 36:44. Just before halfway, reached in 3:02:05, two other Japanese runners, Hayakasha and Gyoba, surged ahead to open a 30-second lead. Kazami opted to maintain a steady pace. By 75 kilometres, the two runners had come back to him. They were both to fade and finish several minutes behind.

Possibly inspired by taking the lead, Kazami posted his fourth fastest 10k split from 70-80km before slowing slightly over the last 20km. Tellingly his last 10km split of 37:55 was crucially quicker than Ritchie and Walmlsley.

Walmsley’s first 10k split seems to be unavailable and is estimated from his 5k and 15km splits. However, he seems to have opted for a strategy of aiming to run pretty much even pace to bring him in just under Kazami’s record around 6:08:30. He ran even pace to 50km, reached in 3:04:14 by which time he had dropped all his other competitors.

His splits indicate he increased his pace slightly between 50k and 80k before falling away between 80 and 90k. As his split times show, he faded over the last 15km. At 90-95 kilometres, many were still predicting he would shade Kazami’s time, but as those who watched the live stream saw, in that last 5km, the extreme effort of running at such an intense pace for 6 hours took its toll.

Don Ritchie’s race, where he ran his 6.10.20 at London’s Crystal Palace track, was one of several ultra-distance track races organised by the UK Road Runners Club and others at this time. These encouraged record attempts at classic distances like 100km and 100 miles. Ritchie didn’t hold back from the start. In a competitive “race“ with that other ultra pioneer Cavin Woodward, they almost blitzed the first 20km with 10 km splits of 34.06 and 35.15 four mins up, relatively, on either Kazami’s or Walmsley’s efforts at 20km.

An enforced pit stop for Ritchie around 25km allowed Woodward to open up a full minute gap, resulting in him having to push hard to catch back up. An effort that he may have paid for later in his race.

The Scotsman just shaded 3 hours for 50 kilometres, some 2 minutes faster than Kazami and 4 minutes faster than Walmsley. Although slowing, by comparison, he was still fastest to 80k (50 miles) and 90km, although only by a mere 30 seconds.

It is the final 10km where all three athletes recorded their slowest 10km of their respective races. The fade by Ritchie, taking almost 40 minutes to cover the last ten kilometres was the most dramatic. He ran roughly 2 minutes slower than the other two.

Walmsley’s even pace meant he was the slowest of all three until 70km, but by 80km, he was then 30 seconds up on Kazami’s time, 4:53:35 to 4:54:10. He was still behind Ritchie’s 4:51:48. The American’s penultimate 10km split kept him 4 seconds inside the Japanese runner’s time at 90k. However, Kazami final 10km split was the fastest of all three efforts in this virtual comparison. It is why he hung on to his record!

So cruel for Walmsley, but the old wisdom of the stopwatch does not lie, is true on this occasion.

Three well-prepared runners separated by just over a minute, and before Sorokin’s effort, the only ones to manage an average pace just inside 6 min mile pace over the distance. However, the splits for all three runners over the last 10-20 kilometres, show that 100k is a distance that needs to be respected, as it can have a nasty sting in the tail.

Hindsight is perfect as always, but managing a steady pace for 100km seems incredibly difficult to sustain, and as Walmsley found, a few seconds banked early in the race to compensate for what seems an inevitable fade may have been beneficial.

Sorokin’s race

Sorokin came into the recent Centurion race in Bedford, in a real purple patch. World Records at 100-miles and 24 hours in the previous 12 months had built on other impressive 24 hr distances in the previous three years.

A 3:02:39 50km in 2021 also indicated he had improved his speed over shorter distances. Would that translate into a fast 100km?

It certainly did, hitting a first 10km of 36:36 slightly slower than Kazami in his record race, but slower than Ritchie’s almost kamikaze 34:06 back in 1978.

Comparing the 50km splits Sorokin, at 3:01:50 was marginally ahead of the split Kazami recorded at Lake Saroma, 3:02:05 but almost 2 minutes down on Ritchie’s 2:59:59 split.

At 80km (49.7 miles) Sorokin with 4:51:58 was now Just over 2 minutes ahead of Kazami’s 4:54:10 split, but just 10 seconds shy of Ritchie’s 4:51:48.

It is over the last 20km that Sorokin maintains pace where previous efforts have slowed. He finally edges ahead of Ritchies 90km split, hitting 5:28:40 to 5:30:45 and is almost 3 minutes quicker than the Scotsman over the last 10km and the best part of a minute faster than either Kazami or Walmsley to close out in that 6:05:41.

Musings on the four fastest 100km times.

Coach’s and armchair analysts will no doubt agonise for hours on what makes the difference. Sorokin’s undoubted, dedication to strength and conditioning that along with his steady year-on-year progress is a principal reason for being able to maintain form in what is that crucial final 20km.

Some will speculate the well-documented “super shoe” factor will have played a part too, but it should be noted both Kazami and Walmsley also wore carbon plate shoes. The runners of the 1970s were in the main using lightweight minimal racing flats!

You can never underestimate the unfathomable factor of inner resilience and confidence built up over many years.

Years of training and intense competition, have enabled these runners to be on a 100km start line, absolutely knowing and believing, if they run smart and fuel well, they are in shape to be close to achieving a record performance.

One thing is for sure, if you could get all four of them mythically around a table chatting away, they would undoubtedly have a huge respect for each other’s respective achievements.

What other factors can one look at

The 4 athletes’ backgrounds. It may just be a coincidence, but all four athletes come from countries where an inbuilt club (UK/Lithuania), college (US) or club/corporate team (Japan) structure is prevalent. All with a history of developing as athletes with regular hard club sessions and year-round pretty competitive race opportunities at a variety of distances. Although hard to find stats on any shorter races Sorokin has run except a recent 15:29 5km, all the others have respectable short distance speed and sub 2.20 marathon times, indicating the ability to hold a fairly intense pace was inbuilt. These are generally acknowledged to be transferable skills for anyone seeking to run a fast road 100-kilometre. Their ages too indicate several years of high volume and high-intensity endurance training and competitive racing had bought them to a level of fitness and conditioning “ready” for the challenge.

SOROKIN WALMSLEY KAZAMI RITCHIE

AGE ON RACE DAY 41 31 35 34

10KM PB U/A 29:08 30:17 30:54

Half marathon PB U/A 1:08:08 1:03:25 1:07:42

Marathon U/A 2:15:05 2:13:13 2:19:34

100km PB 6:05:41 (2022) 6:09:26 (2021) 6:09:14 (2018) 6:10:20 (1978)

A factor worth noting is that 40 years ago, Ritchie lived in a world where there were no financial incentives for ultra runners and nowhere near the level of additional resources that todays ultra runners like Walmsley, Sorokin and Kazami have had access too. He held down a full-time job as a teacher. There were not the perceived advantages in sport science that we have today. He was lucky to have as an Aberdeen AC club member Ronnie Maughan. Maugham was a future professor of Sports Physiology at Aberdeen and then Loughborough University. He would also become an advisor to the IOC, amongst other bodies and was a great source of advice to Ritchie at the time.

Walmsley is a full-time athlete. Kazami certainly seems to have had spells where he was supported by his company, as part of a corporate running team. In effect, a full-time athlete. At other times he held down a regular job while still finding time to train to a stellar level.

Sorokin, almost by default, become a full-time athlete during the Covid Pandemic. His phenomenal performances over the last three years have enabled him to attract sponsors to maintain a full-time athlete status.

Can a course affect performance?

Sorokin’s course was as efficient as you could ever get. A flat, slightly sheltered, 400-metre track. Generally good conditions on the day, but a reported stiff breeze at times.

Ritchie also had the benefit of a stable track environment.

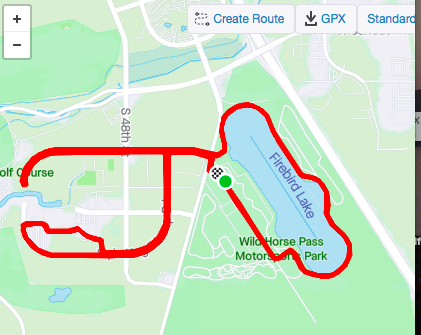

Walmlsey’s course was well-researched by the team behind the Hoka-sponsored event.

It utilized a flat 11km loop run nine times with a short run in and out from the start and the finish on the first and final lap. Any flat identical multi-loop courses usually entail, much like a 400m track, equalizing any possible effect the wind and the elements may have on the runners.

Kazamis Lake Saroma course is what has raised a few eyebrows. It is not flat but has a few minor “undulations” in places. Arguably, this is not a bad thing in moderation in a long road event to give tired muscles some variety. Technically, although it meets the current World Athletics criteria for record purposes, it does have a strange shape. The course looks like a Wok with larger long flat handles.

The start and finish are separated by over 40km. It starts with an out and back approx 15 km section and finishes with a similar out and back10km section. These two parts of the course are joined by a long, slightly curved, 50km loop, the curved Wok-like section. It goes around one side of the lake between 50 and 80km. Other more learned people have commented that this does leave its coastal location open to prevailing winds off the China Sea affecting times. All one can say is that every few years fast times are run. I would stress that it is not the fault of the runners. They just run the course and roll with it.

As always, in any sport, rules evolve with the sport, aiming to maintain a level playing field. It certainly does beg the question if more of these invitational style events are held in future, whether the federations need to take a serious look at whether large, single loops or shorter multi-loops should be looked at for ultra record purposes. An imaginative race organiser or commercial promoter could take advantage of local conditions.

At Lake Saroma, in addition to Kazami’s time in 2018, where for the only time in history 4 other runners ran inside 6.30 in a certified 100km race, Takahiro Sunada ran the previous road best of 6:13:13 in 1998. In 2000 Tomoe Abe, a 2:26:09 marathoner and world championship medalist set the current women’s record of 6:33:11 in 2000.

Comparing records and Best Performances

In a footnote, it is interesting how World Athletics rules apply to ultra-distance running. The International Association of Ultra Runners (IAU) keep and ratify all the recognised ultra distances from 50k to 1,000 miles and beyond. These include best marks run on a road or track as long as the distances are accurately measured.

World Athletics, the global athletics governing body, have recognised 100km as a legitimate record distance for many years. They have also recently acknowledged 50km as a ratified distance for records. However, like the standard marathon distance, they only recognise marks set in certified road events. Ritchie’s time of 6:10:20 was run on a track. It was classed as the best performance and never recorded as the world record. The slower road marks of the Japanese athletes Sunada and Kazami were acknowledged.

The IAU is currently liaising with World Athletics for other notable ultra performances, like Sorokin’s track marks, to be listed either separately or at least as“Best Performances”, if they will not acknowledge them as records.

Can anyone else threaten this record?

There has been much interest and chatter in mainstream sports media and various social channels. Coaches and athletes are sure to be having a fresh look at 100k as an event and thinking about what is achievable.

Who could be capable of going faster at this fascinating distance? As alluded to before, history and logic will tell you it would need to be someone with competent speed endurance credentials with experience of holding an intense pace, if not at 100k, certainly up to 80km previously.

Any British Challengers?

Of current British Athletes, someone like Tom Evans comes to mind. Like our four athletes featured here, he has good speed at 5k to half marathon, with the ability to run hard and fast for several hours, as his long trail running success at events of up to 100 miles show. He has a similar background to Jim Walmsley’s. In 2019 Dan Nash transitioned from the marathon to 50 kilometres. He ran 2:49:01 to break Jeff Norman’s longstanding GB record showing he could have the credentials.

Whether they would want to devote a period of quality training for that opportunity, above other targets, time will tell.

What qualities could be needed?

Sorokin has put in the hard graft over several years to get to a position where he has demonstrated the capacity to go long. His 100-mile and 24 hr performances are outstanding. He has also now developed the speed endurance to run a good 50 km and an excellent 100 km. It is a phenomenal range for an ultra runner to excel from 50km to 24 hours.

The influence of the mental side of ultras should not be underrated either. The last 10-20km of these athletes’ races show the ability to stay strong and focused when your body is falling apart. When that supposed inbuilt “governor theory” sends signals to you that you are entering into and beyond that red zone and telling you to ease back or stop.

So a strong resilience and the ability to endure pain not just for the last two laps but the last two hours, are essential qualities.

Ritchie, correctly, always felt a Japanese or a South African could challenge his time. The Japanese because they know how to prepare well for 100km and have the inbuilt “warrior spirit“ essential to push through when things became interesting.

He also felt the South Africans could, because of their history with the 90k Comrades Marathon. The financial incentives of Comrades appear to be too much of an influence compared with the 100km. Fast Comrades runners have, to date, never really transferred that to a stellar 100k time.

It was an interesting observation coming from a European angle, but Sorokin did not fit that profile. Probably because in the last 20-30 years things have moved on, and ultra running has become a truly global discipline. There are world-class performers on every continent now. As things develop, the new record-breakers are more likely to appear out of nowhere.

Someone, obviously with some natural talent and, ideally, with a solid personal support structure in place, will be nurturing a dream. Like all the four athletes mentioned here, it will need a few years of dedication and hard graft. Mistakes will be made along the way, but the next holder of the 100k record is out there. It may be an already-known name or an as-yet-unknown one. That is one of the great things about the sport.

As Ritchie confided once, “I was able to run 6:10:20 off a 2.19 marathon PB. Someone with sub 2:10 marathon speed could certainly threaten the 6-hour barrier. They would need to develop endurance and learn how to prepare for a 100km. They would then need to pace a race well ”.

That would be interesting to see.

Complete 100km World All time list

You can see the complete 100km Word All time list at the DUV Ultra stats site

PLEASE SHARE!

Thank you for reading this far. If you have enjoyed this post, do see our others ones HERE

If your inspired by this or think someone else you know will be, please do what you have to do by way of sharing, signing up to the mail or RSS feed or leaving a comment below. You all know how these things work by now :-). You can also follow me on twitter and insta @tarittweets Adrian Tarit Stott

READ MORE OF MY BLOGS

.

Adrian Tarit Stott.

The author is a former GB 24 hour ultra international with over 100 ultra race completions. He has also been involved organising ultra distance races for over 30 years. Still an active recreational runner, he is currently a member of UKA’s Ultra Distance Advisory Group (URAG) and part of the selection and team management for both Scottish and GB ultra teams.